This article is reproduced from Ka Jingshai – The Light, a biennial e-zine (also a printed magazine) published from Ramakrishna Mission, Shillong in Khasi, English and Hindi languages. The magazine portrays the culture and spirituality of Meghalaya in a universal context through art, poetry, literature and humour. Ka Jinghsai is the first e-zine of Ramakrishna Order in Khasi. Subscription to this e-zine at https://kajingshai.rkmshillong.org is free.

Swami Vivekananda’s life has been well-studied, but details about some of the things he did continue to surprise us. Can you picture him conversing in English with a hill mynah in the middle of New York City—or singing in Norwegian?

One of Swamiji’s very devoted friends and supporters in New York was Emma Cecilia Thursby (1845–1931). She was a classically trained singer, and she had a very successful career as a concert soloist during the 1870s and 1880s, traveling throughout Europe and North America. She had an incredible three octave range and she could sing difficult arias by Mozart such as “Der hölle rache” and “Ma che vi fece, o stelle” with ease. After her London debut in 1879 The Times wrote:

“Her voice, a high soprano, is sympathetic, and her method singularly free from all mannerisms. . . . the production of the voice, especially in the higher registers, is remarkable for its ease and absolute purity of intonation.”1

During the winter of 1895 Miss Thursby and her close friend Sara Chapman Bull (1850– 1911) arranged several lectures for Swamiji in New York City. It was an intensely busy period for him, teaching classes in the morning and giving lectures in the evening. It was also a busy and fruitful period for Miss Thursby, as her biographer noted:

“The Vedanta philosophy of Vivekananda had, indeed, aided her in at last reaching a strong conviction in her usefulness. She would henceforth devote her life to teaching of that art of singing in which her achievements had been so brilliant; to that art of friendly intercourse in the spirit of which her “Fridays” had already been established; and to that art of kindness and compassion and sacrifice to which so much of her life had already been dedicated.”2

Miss Thursby formerly sang at the Broadway Tabernacle, a large church close to Swamiji’s rented rooms at 54 West 33rd Street. In later years, between 1905 and 1911, she was a professor of music at the Institute of Musical Art (now Juilliard School) in New York.3

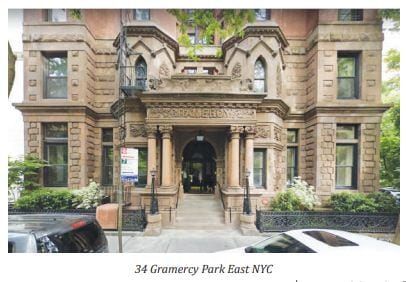

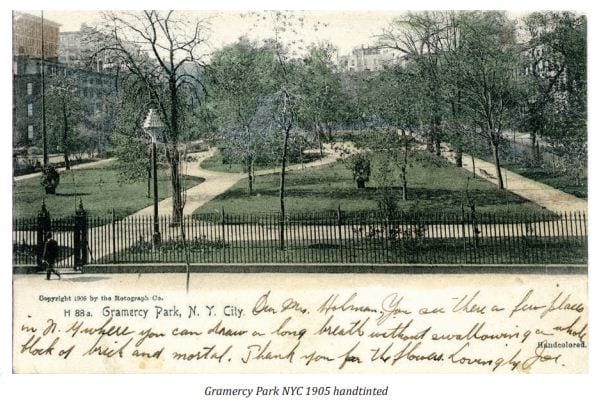

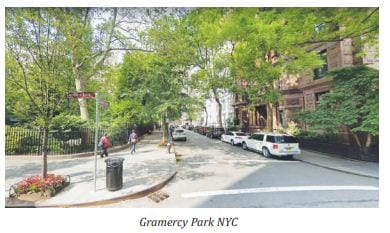

On Monday 28 January Swamiji gave a talk in Miss Thursby’s drawing room. She lived at 34 Gramercy Park East. Gramercy Park was the first planned residential development on Manhattan, begun in the 1830s. It resembles the green squares of London where elegant terraced houses surround a small park bound by a wrought iron fence. Gramercy Park is Manhattan’s only private, gated park. The neighborhood has long been popular with actors and performers. No. 34 still stands at the corner of East 20th Street and Gramercy Park East, and its distinctive facade remains original. Built in 1883, it was New York’s first co-op apartment house with its own Otis elevator. The original elevator, the one that Swamiji would have used, was replaced in 1995.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle featured Miss Thursby and her most famous student, Geraldine Farrar, in an article on 27 July 1924. It described her concert career, her voice, and the cultured life in her Gramercy Park salon:

“In her home in Gramercy Park, one of the few remaining spots in Manhattan that retain the charm of old New York, Miss Thursby holds a salon, which is said to represent more truly than any other in the whole country the salon of the Beau Monde, Paris. In a spacious, low-ceilinged drawing room that is filled with art treasures, souvenirs, gifts from all over the world, Miss Thursby and her sister, Miss Ina Thursby, receive on Fridays in January. At one end of this big room hangs a life size portrait of Miss Thursby by George P. A. Healy, an American painter who received important recognition in Paris. At these at homes one meets a cosmopolitan company, among whom are stars of the opera and the theater, authors, painters, sculptors, scholars, diplomats, statesmen, social leaders and persons of distinction in different activities from all over the world. . . .

Also among the guests from the Far East were Tagore, Das Gupta, Suami Viva Kananda, the Begum of Janpira and her sister, the Princess, who are thoroughly familiar with Hindu music, in which Miss Thursby also takes a keen interest. One of her most diverting experiences, musically, was in teaching Viva Kananda to sing the songs of Grieg with the quality of voice in which he recites his Sanscrit chants, which, she says, is rarely beautiful.”4

Lillian Edgerton, the journalist who interviewed Miss Thursby, wrote of Swamiji in the present tense, as if he were still alive in 1924. It is quite possible that Miss Thursby gave her that impression, and it indicates that Swamiji remained a living presence in her life.

Emma Thursby and Sara Bull were bonded not only as friends but also as artists. They were like musical sisters. In the early 1870s Miss Thursby and Norwegian violinist Ole Bull had performed in concerts together. Ole’s young wife, Sara, would have accompanied them on the piano, perhaps not on the stage, but certainly they spent many hours making music together in rehearsal and at home. Swamiji was frequently a guest at Sara Bull’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In that pre-electronic era the piano played a fundamental role in middle-class homes. It was as important as the hearth. Although Swamiji sometimes complained of “thumping” on the piano when he stayed with people who merely played pop songs, the music that filled the homes of Mrs. Bull and Miss Thursby was artistry of the highest order.

It is fascinating to contemplate the musical exchange between Swamiji and Miss Thursby. He taught her the theory of Indian music, and she taught Swamiji to sing some songs by the Norwegian composer, Edvard Grieg. Ole Bull had mentored Grieg when he was a teenager. After Ole’s death, Sara Bull kept in touch with his Norwegian compatriots and fellow artists. By 1895 Grieg had established a high reputation as Norway’s leading composer. His style was Romantic and nationalistic— probably a very good musical choice for Swamiji. There is no mention of which songs Swamiji may have practiced, but the dignified, meditative “En Svane” is a good example to listen to. Swamiji’s voice, according to written descriptions, was rich and deep—probably in the baritone range.

It stands to reason that Swamiji visited 34 Gramercy Park East many times. And during his visits there he must have met Mynah because “Mynah ruled the household.”5

Mynah was a remarkable bird and personality. “He spoke grammatically and often with disconcerting fluency in five languages:” English, French, German, Malay and Chinese.6 He could sing songs, mimic the banjo, and play melodies on the piano by stepping on the keys. This Mina (sic) was loquacious, weirdly knowing, vain and snobbish.”7 Mynah had his own room and was treated more like a child than a pet. Swamiji especially liked animals, and I can imagine him conversing with Mynah like he was an old friend. Thursby had adopted him in Ems, Germany about 1887. The German ambassador to China, who had acquired the bird in India, gave him to Miss Thursby and instructed the bird to stay with her.8 Henceforth, Mynah called Miss Thursby “Mamma.”

Mynah travelled wherever Miss Thursby went. She would let him fly free when they went to places like Green Acre, Maine. Sarah J. Farmer was very fond of Mynah, and she wrote a letter praising the bird.9 It is possible that Swamiji first met Mynah at Green Acre in 1894, as did Swami Abhedananda in 1898. Mynah was surely welcome at Sara Bull’s houses at Green Acre and in Cambridge. Mynah loved to play in Gramercy Park. He would watch the children from the window and would beg, “Mamma, mamma, I want to get out! I’ll come right back.” This, however, Miss Thursby seldom allowed because Mynah had once been stolen from Gramercy Park, and she had had a terrible time getting him back.

An article in the Washington D.C. Evening Times stated that both Swami Vivekananda and Swami Abhedananda admired Mynah.

“It is a marvel,” said they; “a fit bird to perch upon the sacred finger of Lal Rao. Peace be unto it.”10

While it is good to have confirmation in print that Swamiji appreciated Mynah, it is bizarre to think of him reverencing a deity called Lal Rao. Either the journalist misunderstood whatever he was told or clearly fabricated this “sacred finger of Lal Rao” business. Who was Lal Rao? In the 1890s the only Lal Rao known to Americans was a fictional character, the Indian butler in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s second Sherlock Holmes mystery, The Sign of the Four. Although this journalist got his facts scrambled, I think it can be assumed that on separate occasions Swamiji and Swami Abhedananda said nice things about Mynah.

On 1 December 1898 Mynah made a celebrity appearance at the New York Ornithological Society show, delighting the crowds. Later, at home, he gave his last interview to a journalist from the New York Herald who declared him the “Smartest Bird in the World.”11 On 30 December, he entertained a group of underprivileged children.12 Shortly after that, Mynah, who was about fifteen years old, became ill and died 27 January 1899, pitifully crying in French “au revoir.”

Mynah’s strange existence soon got even stranger. Postmortem, the bird was autopsied by three physicians—none of whom were veterinarians or ornithologists. They determined that Mynah died of spinal meningitis and that his brain and vocal chords were unusually large. Then Mynah was stuffed by a taxidermist and he was exhibited under a bell jar in Miss Thursby’s apartment. In time, she apparently relinquished her attachment to Mynah’s feathered form. When she was interviewed in 1924, she said that Mynah was buried under a willow tree in Gramercy Park.13

The story of Mynah’s death was reported in newspapers all over the country. It gained a lot of attention in Hawaii. South Asian mynahs were introduced to Hawaii in 1865 to control an infestation of army worms. This worked as a temporary measure, but as the birds thrived, the environmental balance was upset—as often happens with the introduction of non-native species. By 1899 Hawaiians were agitated because mynahs were accused of spreading another invasive species, lantana, by eating and excreting its fruit. The mynahs of Hawaii were common mynahs (Acridotheres tristis tristis). It is believed that Miss Thursby’s Mynah was a hill mynah (Gracula religiosa), a bird that is currently endangered in Meghalaya, India.14

Problems of conserving wildlife now confront every country on the planet. In Swamiji’s day, bird populations in America were being decimated to provide feathers for the fashion industry. During the mid-1890s ladies hats were often decorated with entire birds. Such ostentatious display was everywhere that Swamiji went. Even Mynah must have noticed it. Especially hard hit by this greedy slaughter for feathers were the Florida snowy egrets, members of the same family of birds that inspired Ramakrishna’s first samadhi as a boy. Little Gadadhar went into ecstasy when he saw a flock of beautiful shada bak flying freely against dark rain clouds. So much depends upon the beauty of birds!

In February 1896 two Boston women organized the Massachusetts Audubon Society to stop the killing of egrets for hat decoration.15 (One of the Vice-presidents was Mrs. Louis Agassiz who had helped arrange Swamiji’s lecture at Radcliffe College.) Protective laws such as the Lacey Act of 1900 began to change the exploitative mindset of the culture. The sale of wild bird plumes was outlawed in 1910. Eventually, women—aided by the apocalypse of World War I—ended the fashion for feathered hats.

Worldwide, the hill mynah is not considered threatened, but locally there is cause for concern. They are “virtually extinct in Bangladesh due to habitat destruction and overexploitation for the pet trade.”16 This scarcity has now spread to north-eastern India. Hill mynahs live and breed in the upper forest canopy. They are very difficult to breed in captivity. If hill mynahs were easily bred in captivity, then there would be no incentive to capture them from the wild. Therefore, current suppliers to the pet trade need to abide by sustainable practices or there will be no future for them.

The extinction of the passenger pigeon is a cautionary tale. Native to North America, it was once the most abundant bird population in the world. The birds traveled in flocks so large that they blotted out the sun when they flew overhead. People killed them by the thousands—partly to eat, but mostly just for “sport”. They did not believe that such a plentiful creature could disappear from the earth. Yet a population counted in the hundreds of millions in 1871 had shrunk to just dozens by 1895. The last passenger pigeon died in 1914. When Swamiji was at the World’s Fair in Chicago, Americans shocked by their own wastefulness were trying to explain to themselves the near extinction of the buffalo.

Miss Thursby’s pet Mynah was beloved, but in one important respect he had a lonely existence. Mynah never had any relationship with his own kind, and that is the fate of most birds sold into the pet trade.

Photo Courtesy

1) Common Hill Mynah. Wikimedia Commons. Nafis Ameen.

2) 34 Gramercy Park East: Google Maps

3) Swami Vivekananda in New York 1895: Vedanta Society of St Louis

4) Emma Thursby: Library of Congress

5) 1905 handcoloured postcard of Gramercy Park: Courtesy of Vivekananda Abroad Collection

6) Gramercy Park: Google Maps

References

1) Richard McCandless Gipson, The Life of Emma Thursby (New York: New York Historical Society, 1940), 191.

2) Ibid. 369.

3) bid. 374.

4) Lillian Morgan Edgerton, “Emma Thursby, Greatest Concert Singer of Her Time”, Brooklyn Daily Eagle (27 July 1924), 33.

5) “This bird spoke five tongues”, Spokane Chronicle (9 February 1899), 4.

6) Ibid.

7) Ibid.

8) J A Fowler, “A Remarkable Singer and Her Talented Bird Mynah”, The Phrenological Journal (New York: September 1899), 286.

9) “Praise for a Songbird”, The Evening Times (Washington DC: 5 September 1899), 3.

10) “An Autopsy on a Remarkable Bird”, The Evening Times (Washington DC:February 1899), 6.

11) “Smartest Bird in All Creation”, New York Herald (4 December 1898), 3.

12) “Death of a Bird of Marvelous Song”, The Evening Times (Washington DC: 31 January 1899), 2.

13) Edgerton, “Emma Thursby”, Brooklyn Daily Eagle (27 July 1924), 33.

14) Swathi Diwakar, “Meghalaya State Bird Faces Extinction—Hill Mynah”, The Telegraph (16 November 2006), accessed 16 February 2020.

15) William Souder, “How Two Women Ended the Deadly Feather Trade”, Smithsonian Magazine (March 2013), accessed 17 February 2020.

16) “Common Hill Mynah”, Wikipedia, accessed 18 February 2020.

Source : Vedanta Kesari, June, 2020

Leave A Comment