Transformation is a Process

There have been at least two major instances in the world where in each case a Master chose his messenger and transformed him into a formidable apostle.

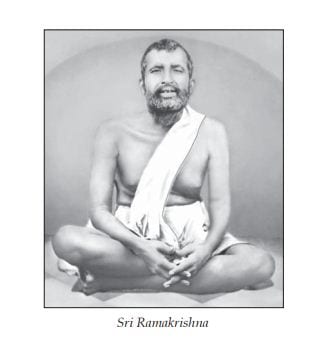

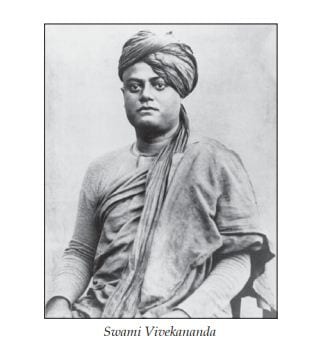

One happened in the first century when a resurrected Jesus Christ revealed Himself to Saul, more commonly known as St. Paul, chose him to proclaim His Gospel to the world, and instantaneously transformed his life. Nearly two millennia later, Sri Ramakrishna transformed his favorite disciple Narendranath into Swami Vivekananda for the same purpose. The difference is that in the latter instance, the transformation was gradual and it continued even after the Master left the mortal world.

Transformation is a process, and in Vivekananda’s case it was subtle. It fully manifested itself in the West when he completely immersed himself in the role of a ‘World Teacher’ and actualized his Master’s proclamation: ‘Naren will teach others.’

To give readers some idea of this gradual transformation, we will choose a snapshot of the day when the Master and the disciple discussed the subject of God and His incarnation and a few other related topics in the presence of other devotees of the Master, some of whom also participated in the discussion.

An Insightful Conversation

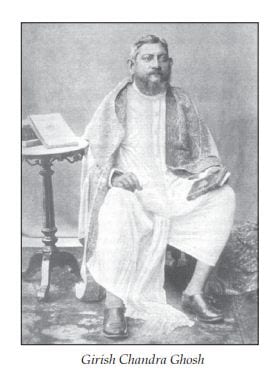

The day was March 11, 1885, and what transpired that day at Girish Ghosh’s house in Calcutta has been well-documented.1 The day is significant, because it is the first time in the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna that we find the Master and the disciple engaged in backand-forth conversation on a very important subject that establishes what Narendranath’s thinking was at that time. We can see how the Master softly countered his disciple’s views without showing the faintest sign of being contentious—it was a lesson with intense love and empathy. We will see how that lesson, and probably many others like it, both public and private, changed Narendranath’s views on the topics discussed on that day.

According to the Gospel, Sri Ramakrishna went to Balaram Bose’s house on that day. There he met Girish Ghosh and others and a conversation ensued on the subject of God’s infinitude. Girish’s view was that God could incarnate himself in a human body. Narendranath wasn’t there then, but when challenged by Sri Ramakrishna to argue with Narendranath sometime on that subject, Girish gave some indication of Narendranath’s views on it; he and Narendranath had apparently discussed this before.

According to Girish, Narendranath thought God was infinite, and since infinity could not have parts, we could not perceive anyone or anything as being a part of God; in other words, he did not believe in avatarism. Sri Ramakrishna had a different view. He said that even though God was infinite, He could will His essence to be manifested through other beings. This subject was discussed in more details when Narendranath appeared on the scene later that evening.

Girish then took Sri Ramakrishna to his house where Narendranath joined them. Picking up the thread of the previous discussion, Sri Ramakrishna wanted Girish to argue with Narendranath on the subject of incarnation in his presence in English. Not that he didn’t know their views on the subject, but it was his way of getting into the discussion and to express his views for Narendranath to note and test in the crucible of his disciple’s own reason. Sri Ramakrishna knew the truth, but he did not want to impose it on Narendranath, but to let him think and make his own decision. But instead of in English, the argument started in Bengali, and this is how ‘M’ presented in the Gospel the conversation that followed on the subject (with the author’s few comments in between):

Narendra: God is infinite. Are we capable of comprehending Him? He is in everybody—not necessarily in one person. Sri Ramakrishna ( affectionately) : He [Narendranath] and I are of the same opinion; God is present everywhere. But we must remember one thing that His power is not manifested the same way everywhere. In some places it is manifested as Avidyashakti [bad power], and in other places as Vidyashakti [good power]. In some men the manifestation is greater, and in others it is smaller. All men, therefore, are not equal. [He apparently meant that the manifestation of good power is the greatest in an avatar, but didn’t come out and directly say so.] Ram: What will come of this useless argument? Sri Ramakrishna (irritably): No, no, there is a meaning in this. [He was still waiting to hear Narendranath’s logic behind his statement.]

Girish (addressing Narendra): How do you know that God does not come assuming a human body [as an incarnation, or avatara]?

Narendra: He [God] is beyond speech and thought.

Sri Ramakrishna [interjecting himself into the conversation between Girish and Narendranath]: No, He can be known by shuddha-buddhi [pure intellect]. Shuddha-buddhi and shuddha-atma [pure Self] are the same. The seers perceived shuddha-atma through shuddha-buddhi.

Girish (addressing Narendra): Who will teach men if there is no human incarnation of God? He assumes a human body to impart to men divine knowledge and piety. Who will teach them otherwise?

Narendra: Why? He [God] will teach us from within our heart.

Sri Ramakrishna: Yes, yes, He [God] will teach as the all-knowing dweller in our hearts.

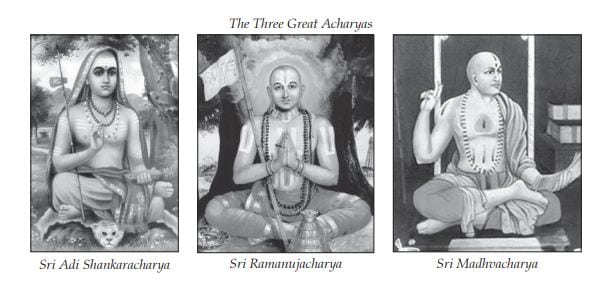

A huge argument then followed where participants quoted various Western philosophers’ views on God’s infinitude. It seems that Narendranath was on one side and the rest on the other. Sri Ramakrishna did not like the nature of the argument and said so at that point. Referring to Shankara’s Advaita, or Non-dualism theory (he knew that was Narendranath’s philosophical leaning), he said that is true and so also is Ramanuja’s theory of Qualified Non-Dualism.

When Narendra questioned him on the latter, he explained it by saying that according to this theory all three—Brahman, the world, and the living beings—collectively represent One Divine Entity. He then drew the analogy of a bel (or bael) fruit. The complete fruit consists of the flesh, seeds, and the shell— all three. One cannot conceive of the whole fruit by considering only the flesh (which is analogous to Brahman according to Sri Ramakrishna); he has to consider the seeds and shell as well. So it is with One Divine Entity and its three components.

Sri Ramakrishna’s point was that one would keep on arguing about the omnipresence of God until one realizes Him. Reasoning would lead to one kind of knowledge, meditation will lead to another, but there is still another kind of knowledge about God that is acquired when He reveals His incarnate presence to the aspirant. The Master then called Narendranath to his side and affectionately enquired about his well being. Their conversation went on.

Narendra (addressing Sri Ramakrishna): I have meditated on Kali for three days, but nothing happened.

Sri Ramakrishna: It will happen gradually. Kali is none other than Brahman Itself. She is Adyashakti (Primal Energy). When that Energy remains passive, I call it Brahman. When It creates, sustains, or destroys, I call it Shakti or Kali. What you call Brahman, I call Kali.

Sri Ramakrishna then impressed upon Narendranath that Brahman and Kali are one and the same; one cannot think about one without thinking about the other, just as one cannot think about fire without thinking about its power to burn. With love overflowing in his heart for Narendranath he then sat close to him and told him that he did not like to hear them arguing about God; there will not be any argument once God is realized. He probably felt sorry for Narendranath because everybody, including himself, was on one side and his favorite disciple was on the other. The conversation on that particular subject ended for that day.

Some Observations

A few things become apparent from the conversation that evening. It is hard to explain Sri Ramakrishna’s motivation for asking Girish to debate Narendranath on the issue of God’s incarnation. He was somewhat aware of Narendranath’s views on it (Girish had also told him earlier that evening). If this was supposed to be a teaching session to persuade Narendranath to change his views, then why did he say in the end that he did not like hearing them arguing? He wanted Girish and Narendranath to have that argument, didn’t he?

There could be several explanations for that. First, maybe Sri Ramakrishna wasn’t sure of Narendranath’s views on the subject at the time and wanted to hear it from his own mouth. Once he heard it he didn’t like it, and went ahead on a teaching mode presenting his own views hoping to persuade Narendranath, and anybody else in the audience, to change his.

Second, great men are known to live lives of continual paradox (at least this is how it appears to a casual observer) and Sri Ramakrishna was no exception. Since he had gone into an ecstatic mood upon seeing Narendranath, he might have forgotten that he was responsible for starting the debate in the first place. One thing is obvious from the exchanges between the Master and his favorite disciple: according to Sri Ramakrishna, Narendranath had not yet realized God.

There is, however, a third explanation that is more mundane. Sri Ramakrishna had initially wanted them to argue in English and hoped to derive some amusement out of it. But when the debate started in Bengali and got quite heated, he regretted it.

As far as Narendranath’s transformation was concerned, the conversation that evening was very significant. Some views he had expressed never changed much as his transformation to Swami Vivekananda gradually progressed. One of those was his idea of a teacher’s role. When Girish said that God assumes a human body to teach men, he said man learns from within (and does not need to be taught by someone else). This concept is implicit in Vivekananda’s oft-quoted, insightful definition of education years later: ‘Education is the manifestation of the perfection already in man.’2 He also said later,

No knowledge comes from outside; it is all inside, what we say a man ‘knows’, should, in strict psychological language, be what he ‘discovers’ or ‘unveils’; what a man ‘learns’ is really what he ‘discovers’, by taking the cover off his own soul, which is a mine of infinite knowledge.3

A corollary to this, though it appears somewhat paradoxical, is that no one can teach anybody. This is how Vivekananda explained it:

Each of us is naturally growing and developing according to his own nature; each will in time come to know the highest truth, for after all, men must teach themselves. . . Do you think you can teach even a child? You cannot. The child teaches himself. Your duty is to afford opportunities and to remove the obstacles.4

Actually, Sri Ramakrishna’s and Vivekananda’s views on this point can be reconciled if one assumes either that the knowledge from within comes from realizing God within, or the teacher (God Incarnate) does not really ‘teach’ but affords opportunities to learn and remove obstacles toward that learning. Then the only major bone of contention between the two is Narendranath’s reluctance to believe that God may come to the world inhabiting a human body to impart divine knowledge to human beings and teach how to get nearer to God. This point, and how Narendranath’s view on that changed with time will be discussed later.

A Great ‘Discovery’

It is somewhat perplexing to find Narendranath questioning his Master about the Qualified Non-Dualism theory of Ramanuja. It is hard to imagine that he did not know the answer himself even if he did not subscribe to the theory. Then why did he ask? He probably did that to test his Master’s knowledge of it, and to understand how it relates to the ongoing argument. His Master definitely left an impression on his mind, because years later, in May 1895, he wrote to Alasinga Perumal from America,

Now I will tell you my discovery. All of religion is contained in the Vedanta, that is, in the three stages of the Vedanta philosophy, the Dvaita, Vishishtadvaita and Advaita; one comes after the other. These are the three stages of spiritual growth in man. Each one is necessary.5

It is not known exactly when he ‘discovered’ it. Still later, in February 1896 in Brooklyn, New York, he said about the three schools of Vedanta Philosophy, Non-dualism (Advaita), Qualified Non-Dualism (Vishisthaadvaita), and Dualism (Dvaita):

Now, as society exists at the present time, all these three stages are necessary; the one does not deny the other, one is simply the fulfillment of the other. The Advaitist or the qualified Advaitist does not say that dualism is wrong; it is a right view, but a lower one. It is on the way to truth; therefore let everybody work out his own vision of this universe, according to his own ideas. Injure none, deny the position of none; take man where he stands and, if you can, lend him a helping hand and put him on a higher platform, but do not injure and do not destroy. All will come to truth in the long run. ‘When all the desires of the heart will be vanquished, then this very mortal will become immortal’—then the very man will become God.6

That definitely points to a transformation. The Master always said that one would realize God when all material desires are vanquished. Vivekananda said the same thing, only he equated realizing God with becoming God.

Two Important Questions

The two important questions from the conversation still remain:

First, did Vivekananda accept Sri Ramakrishna’s statement, ‘Kali is none other than Brahman Itself . . . What you call Brahman, I call Kali?’ Did he equate Kali with Brahman? Did he equate form with formlessness?

Second, did he believe in avataras? And, if so, did he believe that Sri Ramakrishna was an avatara?

The answer to the first question is: yes, Vivekananda later came to believe that Brahman and Kali are the same, but with some qualifications. As a member of the Brahmo Samaj, Narendranath was committed to belief in a formless God with attributes. Sometime during his early Dakshineshwar days he took Rakhal (Swami Brahmananda) to task for bowing down before the images; he was trying to persuade Rakhal to give up the worship of God with form and embrace the Brahmo creed. When Sri Ramakrishna came to know about that he said to Narendranath, ‘Please do not intimidate Rakhal. He is afraid of you. He believes now in God with forms. How are you going to change him? Everyone cannot realize the formless aspect of God at the very beginning.’ Narendranath never interfered with Rakhal’s attitude after that.7 Although he talked mostly about the formless in the West, he reconciled with his Master’s statement even before going to the West.

In Madras (in 1892-93) he said, ‘Form and formless are intertwined in this world. The formless can only be expressed in form and form can only be thought with the formless. The world is a form of our thoughts. The idol is the expression of religion . . . In God all natures are possible. But we can see Him only through human nature.’8 Sri Ramakrishna saw Mother Kali—the formless in thought appeared to him as form.

Even earlier during his itinerant days in Rajputana, Vivekananda had talked about Mother-worship and chanted mother’s name in an ecstatic state.9 And who can forget the evening when in a highly exalted mood he wrote the poem ‘Kali the Mother’ and then collapsed ‘while his soul soared into BhavaSamadhi.’10 Although he was reticent about his spiritual encounter with the formless, he did not hide his feelings about form.

Now we come to the resolution of the second question: did Narendranath believe in avataras? (Whether he believed Sri Ramakrishna was an avatara or not depends on the answer to this question.) We have seen on March 11, 1885, that he didn’t. Once when Narendranath demanded proof that God assumes a human body, Girish Ghosh said faith is the only proof.11 Somewhere along the process of transformation the proof was probably revealed to him, but he never mentioned where and how. We see that his view softened significantly by March 1890, exactly five years later, when he wrote to Pramadadas Mitra:

So now the great conclusion is that Ramakrishna has no peer; nowhere else in this world exists that unprecedented perfection, that wonderful kindness for all that does not stop to justify itself, that intense sympathy for man in bondage. Either he must be the Avatara as he himself used to say, or else the ever-perfected divine man, whom the Vedanta speaks of as the free one who assumes a body for the good of humanity. This is my conviction sure and certain.12

Here Vivekananda mentioned Sri Ramakrishna as an avatara, but he did that indirectly.

After returning from his first visit to the West, Vivekananda’s conversation with disciple Sarat Chandra Chakravarty went like this:

Disciple: Do you, may I ask, believe him to be an Avatara (Incarnation of God)?

Swamiji: Tell me first—what do you mean by an Avatara?

Disciple: Why, I mean one like Shri Ramachandra, Shri Krishna, Shri Gauranga, Buddha, Jesus, and others.

Swamiji: I know Bhagavan Shri Ramakrishna to be even greater than those you have just named. What to speak of believing, which is a petty thing—I know! Let us, however, drop the subject now; more of it another time.

After a pause Swamiji continued: ‘To re-establish the Dharma, there come Mahapurushas (great teachers of humanity), suited to the needs of the times and society. Call them what you will—either Mahapurushas or Avataras—it matters little.’13

Here Vivekananda acknowledged that avataras may come as teachers, but stopped short of saying that Sri Ramakrishna was an avatara. When pressed by the disciple why didn’t he preach Sri Ramakrishna as an avatara while others did, his answer was to let others do it in the light of their understanding of him.

He said he understood him very little, and was afraid of belittling the great personality by painting him in the light of his own understanding of him. It seems that he, in his heart of hearts, accepted Sri Ramakrishna to be an avatara, but did not preach him as one. He was probably afraid of starting a ‘Ramakrishna cult’, a term that was coined by the Western Press anyway.14

As his transformation progressed, we have seen how Narendranath’s views changed on the infinitude of God, the concept of avatara, and accepting Sri Ramakrishna as one. Although he never publicly preached that Sri Ramakrishna was an avatara, in 1898 he paid his greatest homage to Sri Ramakrishna as one by writing the obeisance mantra [pranam-mantra] at the end of Sri Ramakrishna-Stotram that is chanted in homes and institutions all over the world: ‘Om! Obeisance to you, Ramakrishna, establisher of dharma, embodiment of all religions, foremost of Avataras.’

As Swami Vivekananda, he finally acquiesced.

The conversation on March 11, 1885, at Girish Ghosh’s house would have taken a much different turn if Narendranath had recited it then.

References

- Sri M, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita, (Udbodhan Karjalaya, Kolkata, 1st edition, 1986-87), vol. 1, pp. 769-780, or Swami Nikhilananda, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, (Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras, 1996), pp. 726-735.

- Complete Works, vol. 4, p. 358.

- , vol. 1, p. 28.

- , vol. 2, p. 385.

- , vol. 5, p. 81.

- , vol. 2, p. 253

- Life, vol. 1, p. 94.

- Complete Works, vol. 6, p. 115.

- Life, vol. 1, p. 266

- Life, vol. 2, p. 379.

- Sri M, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita, vol. 1, p. 825, or Swami Nikhilananda, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, , pp. 771.

- Complete Works, vol. 6, p. 231.

- , vol. 5, p. 389.

- The Los Angeles Times, August 3, 1902. Quoted in Swami Vivekananda in America: New Findings by Asim Chaudhuri (published by Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata, 2005), p. 847.

Source : Vedanta Kesari, May, 2015

Leave A Comment