A Historical Perspective

Women as scholars, poets and spiritual instructors were not a new phenomenon in India of the 20th century. As early as the Vedas, they were in the forefront as knowledgeable members of the society. The Vedas had amongst its Rishis many women, among them Ghosa Kaksivati, a granddaughter of the eminent Rishi Dhirgatamas as also Ghodha and Vasukrapatni. As Swamini Atmaprajnananda Saraswati has pointed out, there is nothing in the Vedas to show that women could not be Adhikaris [recipients] of the mantra.

But there was a steady decline in their status due to many reasons. One of them was no doubt the continued foreign invasions and desecration of Indian women by invading armies. The Sati of Rani Padmini and the other ladies of her time are well-known. In trying to keep their women away from the public eye, men proceeded to deny other facilities for them, one of them being education. Women’s position had indeed become unenviable by 19th century.

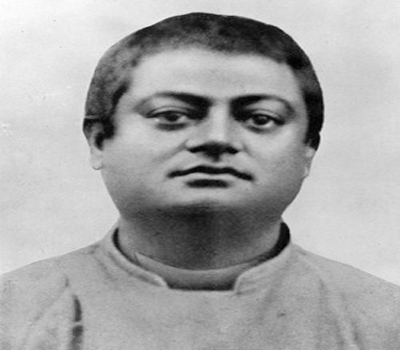

Swami Vivekananda’s travels through the land as a Parivrajaka [itinerant monk] revealed to him this ugly state of affairs regarding the position of women in Indian society. It called for immediate rectification.

According to him, women were not playthings for men, and women’s problems could be solved only by true education, which was,

. . . A development of faculty, not an accu-mulation of words, or as a training of individuals to will rightly and efficiently. So shall we bring to the need of India great fearless women— women worthy to continue the traditions of Sanghamittra, Lila, Ahalya Bai, and Mira Bai— women fit to be mothers of heroes, because they are pure and selfless, strong with the strength that comes of touching the feet of God.1

He realised that education held the key to such empowerment. Towards achieving that he called for the founding of schools and persuaded educated, foreign ladies to come to India and inspire the women here.

Swamiji wanted to get girls into the schooling system to empower them physically and economically. Mentally too, for they should become equal to men in everyday dealings and dare to take decisions on their own. The last part was the direct result of his experiences in England and the United States. The position of American women in their society inspired him no end. He wrote to Swami Ramakrishnananda on 19th March, 1894:

Nowhere in the world are women like those of this country. How pure, independent, self- relying, and kindhearted! It is the women who are the life and soul of this country. All learning and culture are centred in them. The saying, Yaa Sri Svayam Sukrutinaam Bhavaneshu—‘Who is the Goddess of Fortune Herself in the families of the meritorious’ (Chandi)—holds good in this country, while that other, Alakshmeem Paapaatmanaam—‘The Goddess of ill luck in the homes of the sinful’ (ibid.)—applies to ours. Just think on this. Great God! I am struck dumb with wonderment at seeing the women of America. Tvam sri tvam isvari tvam hreeh —‘Thou art the Goddess of Fortune, Thou art the supreme Goddess, Thou art Modesty’ (ibid.). Yaa Devi Sarvabhuteshu Shakti Rupena Samsthithaa ‘The Goddess who resides in all beings as Power’(ibid)—all this holds good here. There are thousands of women here whose minds are as pure and white as the snow of this country. And look at our girls, becoming mothers below their teens!! Good Lord! I now see it all. Brother, Yatra Naaryasthu Pujyanthe Ramanthe Tatra Devataah, ‘The gods are pleased where the women are held in esteem’—says the old Manu. We are horrible sinners, and our degradation is due to our calling women ‘despicable worms’, ‘gateways to hell’, and so forth. Goodness gracious! There is all the difference between heaven and hell.2

He had personally experienced the bounty of the maternal heart in American women. In a crisis, they could take a decision in a split second. One remembers Swamiji sitting on the kerb on the opposite side of 541, Dearborn Avenue in Chicago on 10th September, 1893. He had walked a long way to find the office of the Parliament of Religions and had had nothing to eat for almost a day. The matronly Mary Hale had seen him, had come out of the house to meet him, made gentle enquiries and took him home to give a proper meal. She had then taken him to the Parliament Office and everything moved properly. Swami Vivekananda’s anxiety for such womanhood in India can be seen in many of his writings on the subject. He went on to say:

If I can raise a thousand such Madonnas— incarnations of the Divine Mother—in our country before I die, I shall die in peace. Then only will our countrymen become worthy of their name.3

This is the reason why when we turn to the page of Swami Vivekananda’s women disciples, those in the forefront of the list happen to be women from foreign lands. Foreign ladies were educated, and could command themselves whether married or not and could always be on equal terms with Swami Vivekananda. They could attend his meetings without any inhibition, and could engage in dialogues with him with perfect ease as in the Upanishadic times, could question him and even demur with him. This spirit was most welcome for Vivekananda who wanted no doors to bar the freedom of the human species. In the 19th century, Indian women could not move around freely and could never dream of a master-disciple relationship with a young Sannyasi. This explains why we have women disciples of Swami Vivekananda chiefly from the West.

Swamiji’s Women Disciples in the West

There were many foreign women like Josephine MacLeod, S. Ellen Waldo and the singer Emma Calve who were his admirers but only very few took initiation as his disciples. Among his admirers we could begin with the one who helped him in Boston much before he became famous on 11th September, 1893.

When he came to Chicago in July and realised that the convention was in September, he had a major problem because of his financial condition. He heard that the cost of living in Boston was much cheaper. It was one thousand miles away but Miss Kate Sanborn of Boston whom he had met earlier had given her card and asked him to feel free to apply to her for help if he had any problem. When he contacted her, she wired him to come to her place in the Metcalfe village. A teacher and farmer who readily helped people, Kate introduced him to her friends during the week he spent in her farmhouse called Breezy Meadows. Thanks to her, he gave his first speech in America to a women’s club on 21st August.

Vivekananda left Metcalfe for Boston accompanied by Kate’s nephew Franklin Sanborn. Franklin was a journalist who had a wide circle of friends, one of whom was Dr. John Henry Wright, Professor of Greek classics at Harvard. They both met at Annisquam, forty miles from Boston. The victory march of Swami Vivekananda had begun.

But even as he was in the glowing limelight of adulation, he remembered the suffering womanhood of India. Hadn’t he seen misery and untimely death in his own family? He was sure that the treatment of women by Indian men was inexcusable. This is why even as he started earning money abroad, he made it sure that a portion of it went to a foundation for Hindu widows at Baranagore in north Calcutta. He also thought that Indian women could receive great inspiration if such western women he was seeing in the United States and England could come to India and open up the path to them.

Time Spirit was on his side. The educated women of America were thirsting for more knowledge and the Indian monk’s pragmatic Vedanta fascinated them. There were to be many spiritually-inclined admirers for him in America. They may not have become his direct disciples, but they could remain tuned to his spiritual and compassionate wavelength. Foremost among them is Ellen Hale of Chicago.

When he came to Chicago from Boston and could not locate the Parliament Office, Ellen Hale had noticed the ochre robes of the traveler and had taken him to her house. Mr. and Mrs. Hale took him to meet the Parliament Office and all was well. When grace is in action, what can stop a victorious march?

Later on, when Swami Vivekananda had to stay in America for a few years, it was Mr. and Mrs. Hale who helped him manage his finances. The entire family—George and Ellen, their two daughters Mary and Harriet as also their nieces Isabel and Harriet McKindley— remained devoted to him. They had drawn so close to him that Swamiji would refer to them as Father Pope, Mother Church and babies or sisters. There was plenty of correspondence, punctuated by humour between Swami Vivekananda and these friends.

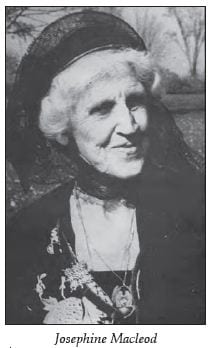

Among other women from the West who played a major role in his work both as helpers and as devotees were Betty Leggett and her husband Frank in whose farm, the sprawling Ridgely Manor at Connecticut, Swami Vivekananda spent a considerable amount of time, during his three visits to the place. The Swami found the place very conducive to meditative life and his longest stay here was for ten months in 1899. It was here that his other devotees like Josephine McLeod (Betty’s sister) and Sister Nivedita also stayed, listening to their master. Even today one can see the sofa on which Swami Vivekananda sat and spoke on Eastern mysticism and global unity to his audience of Western admirers which included Sara Turnbull, Sister Nivedita, Josephine Macleod, Sister Christine and the Leggett couple.

Josephine Macleod

When one goes through Swami Viveka-nanda’s life and his letters, it is obvious that he had many admirers among the western women who had deep devotion for him, admired his stunning capacity to explain Eastern thought in the Western idiom and adored him for his commitment to the social regeneration of the Indian people, particularly Indian women. The one who comes immediately to our mind in this group is Josephine Macleod, a rich aristocratic lady from America.

We are told that it was her material and heroic backing which helped Swami Vivekananda establish this Belur Math. It was also here that Swamiji told her, ‘I shall never see forty’. He assured her that he had given his message and now must go because ‘the shadow of a big tree will not let the smaller trees grow up. I must go to make room.’ Swamiji’s passing was a great shock but she recovered and applied herself in helping the fledgling Mission acquire strong wings by herself staying in the monastery for long periods of time. She also helped in a big way the monks of the Mission who went to the West.

Another foreign friend of Swamiji was a niece of Josephine. Alberta Sturges Montagu who married the 9th Earl of Sandwich was an accomplished musician. Swamiji who could get tuned to others because of his own varied accomplishments, had no problem in communicating with Alberta. This victor of the Parliament of Religions could say the right word in a private letter too as in this epistle to Alberta dated 8th July, 1895: ‘I am sure you are engrossed in your musical studies now. Hope you have found out all about the scales by this time. I will be so happy to take a lesson on the scales from you next time we meet . . .’ He even wrote a poem for her:

The mother’s heart, the hero’s will, The softest flower’s sweetest feel; The charm and force that ever sway The altar fire’s flaming play; The strength that leads, in love obeys; Far reaching dreams, and patient ways, Eternal faith in Self, in all The sight Divine in great in small; All these, and more than I could see Today may ‘Mother’ grant to thee.

(To be continued. . .)

Source : Vedanta Kesari, January, 2015

Leave A Comment