(Continued from previous issue. . .)

This research article throws new light on the initial photographs of Swami Vivekananda taken in America, including the famous ‘Chicago pose’ photograph, and also his sketches in the media.

Swami Vivekananda’s first mention of a photograph made of himself in America comes in a letter to Alasinga Perumal dated 2 November 1893. The first known usage of Harrison’s ‘Chicago pose’ is in the 10 December 1893 Minneapolis Star Tribune. A different rendering of it appeared in the Detroit Free Press on 11 February 1894. Two days later, the Detroit Free Press printed an engraving made from an unknown photograph of Swamiji sans turban showing his short haircut. The bareheaded engraving resembles a photo signed, numbered and dated ’94 by B. L. Snow, indicating that there may have been more poses printed from that sitting.23 Aside from the cabinet cards that Swamiji took with him to Detroit, he wrote to Ellen Hale on 10 March 1894 about a new set of photographs:

‘The photographer here has sent me some of the pictures he made. They are positively villainous—Mrs. Bagley does not like them at all. The real fact is that between the two photos my face has become so fat and heavy—what can the poor photographers do? Kindly send over four copies of [Harrison’s] photographs.’

This set of ‘villainous’ Detroit photographs, like the ‘angry’ photo that Ram Datta had taken of Ramakrishna, have vanished; so we cannot form aesthetic opinions of them. Swamiji’s letter shows that he was not vain about his appearance and that he deferred to the opinions of others regarding his visage.

A publishing rivalry

In Chicago, two rival publishers were hard at work printing their histories of the Parliament of Religions in time for Christmas gift giving.24 Dr. John Henry Barrows, the Chairman of the Parliament, compiled The World’s Parliament of Religions in two prodigious volumes, which were to his mind, the official and definitive record of events. His book was backed by the Chicago Inter Ocean. Any event of epic proportions, however, needs more than one record. The Chicago Tribune backed the volume edited by Prof. Walter Raleigh Houghton and named for its publisher, F. Tennyson Neely: Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions and Religious Congresses at the Columbian Exposition. Unlike Barrows, Houghton was not a Doctor of Divinity. Basically, the Barrows book claimed to be official and authoritative and better quality—it was also more expensive—whereas the Neely book claimed to be impartial and non-sectarian, and it was available for a bargain price. At least readers had a choice. Swamiji himself played absolutely no part in this publishing rivalry, but the inclusion of one of Harrison’s portraits on page 903 indicates that Houghton may have asked him for a photograph. On 5 December 1893 the Tribune announced that Neely’s History was ready for sale.

The standing photograph of Swamiji on page 505 of Neely’s History deserves special consideration. It must have been a second exposure taken at the same time as the previously mentioned group photo of Indian delegates taken at the Fair on 20 September, which appears in Neely’s on page 535. There is strong circumstantial evidence that Blanche L. Snow was the photographer.25 Photography at the Exposition was tightly controlled. Snow photographed people on the Midway Plaisance and she sold thirty photographs imprinted with her copyright to The Werner Company.26 The background was painted out of Swamiji’s page 505 photo, and Neely’s copyright inserted below. The photo of Dharmapala on page 405 received the same treatment. However, when this photo of Dharmapala was printed in a Portfolio published by The Werner Company, it bore Snow’s copyright.27

An engraving was made of Swamiji’s page 505 photo, and it became one of the main illustrations used in the newspaper advertising campaign for Neely’s History. Swamiji stood in the lower right corner beside Kinza Riuge M. Hirai in a full-page ad that ran in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune 15 January 1894. This engraving of Swamiji appeared in newspapers across the country advertising Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions.

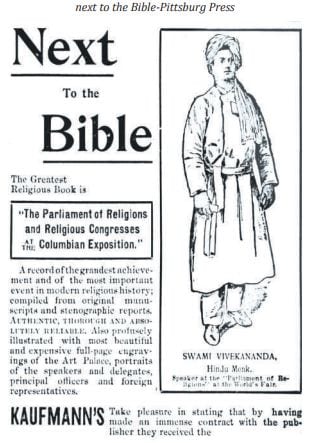

To use Swamiji’s name as part of a celebrity name-dropping campaign and to illustrate him as a colorful delegate to the Parliament was well within the norm for advertising. The advertisement for Neely’s History in the Pittsburg Press, however, went a step further. On 19 February 1894 there appeared this extraordinary headline with Swamiji’s picture: ‘Next to the Bible, the Greatest Religious Book is “The Parliament of Religions and Religious Congresses at the Columbian Exposition.”’ In smaller text in the bottom half of the advertisement (not shown) it said: ‘This book, like the Bible, should be in every house and home.’ Surely advertisers of the nineteenth century were just as canny to product placement as they are today. Due to its visual juxtaposition with Swamiji’s image, this ad implies: Next to the Bible, the Greatest Religious Book is one that contains the words of Swami Vivekananda.

The Philadelphia Inquirer took a more personalized approach to its advertising for Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions, which the newspaper was selling with coupons. On 23 February 1894 the Inquirer featured an article on Swamiji illustrated with the Neely’s engraving of him. Other foreign delegates had been featured in the Inquirer to promote Neely’s History, and of course all of these portrayals were positive and considerate. Even so, the Inquirer’s article endorsing Swamiji was exceptionally glowing.

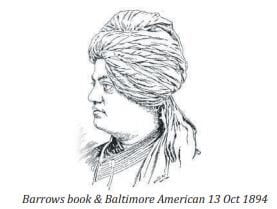

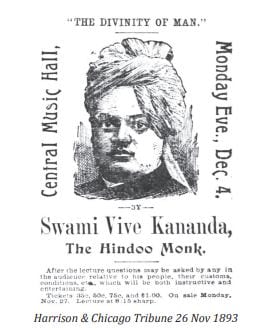

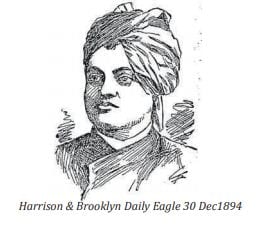

As for Barrows’s book, Swamiji’s photo on page 973 Volume II was used by an artist to create an engraving of him as ‘The Great Brahmin High Priest’ for the 13 October 1894 Baltimore American. The drawing was neatly executed and the artist signed it with the initials S. K. This pattern continued. The Chicago Tribune drew Swamiji from one of the Harrison portraits for a paid advertisement on 26 November 1893. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle drew Swamiji from the Harrison portrait printed on page 903 of Neely’s History on 30 December 1894. On 6 January 1896 the New York World crudely improvised upon one of Swamiji’s 1895 photographs taken by George Prince. On 2 March 1896 the Detroit Free Press illustrated a different Prince photo. Journalists lavished so many words on Swamiji’s appearance that we feel as if we have seen more pictures of him in the newspapers than actually exist. Words were cheap, but engravings cost money and were seldom spontaneous.28

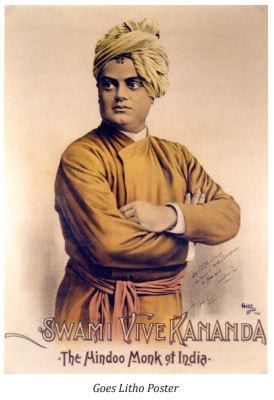

The Goes Litho poster

From the quotidian world of newspapers, we move on to the ephemeral medium of posters. In the spring of 1894 word spread in India of Swamiji’s fame in America. An item in the 12 April 1894 Indian Mirror written by a ‘Hindu friend’ regarding an endorsement of Swamiji made by Dharmapala, stated that Swamiji’s ‘life-size portraits’ were ‘hung up in the streets of Chicago.’29 It further claimed that Americans did ‘obeisance’ to these portraits— which was a misconception. Americans simply did not have the cultural concept of pranama. The image in question, fitting Dharmapala’s description with the words, ‘Monk Vivekananda,’ beneath the figure, was a color poster printed by the Goes Litho Company. It was very likely commissioned by Henry Slayton. I cannot think of anyone else who would have paid for this type of publicity material. Slayton considered Swamiji a financial investment. The posters were no doubt used to advertise his lectures contracted with Slayton.

The 11 November 1893 issue of the weekly New York Dramatic Mirror announced that Swamiji had signed a two-year contract with Slayton Lyceum Bureau. In addition to cabinet cards and pamphlets, advance publicity for Swamiji’s lectures would have included posters. Henry Slayton, who had represented such notable speakers as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, had moved his offices to the Central Music Hall in 1880. Since he was in the same building as Harrison’s photo studio, Slayton was no doubt able to view all of Harrison’s proofs of Swamiji. He must have given a copy of the ‘Chicago pose’ to the poster artist.

Performance posters were time-sensitive materials. Slayton would not have wasted them. They were not posted about the city simply because Swamiji had been a favorite at the Art Institute during the religious congress. Major attractions have dates at the box-office, and in this case the date was 4 December 1893 when Swamiji was booked to speak at the Central Music Hall.30 It is likely that Slayton himself arranged Swamiji’s 4 December lecture because the 26 November ad in the Tribune stated this would be his ‘first public lecture in Chicago’ i.e., his first public lecture in Chicago sponsored by the Slayton Lyceum Bureau.31

In 1899 Swamiji met Mrs. Roxie Blodgett in Los Angeles. Blodgett had attended the Parliament of Religions, and she vividly recalled Swamiji’s impact on the audience.32 She also attended his lectures at the Masonic Temple from 4 to 14 November 1893.33 The date she left Chicago for California is not known, but she hung one of these large posters of Swamiji on a wall in her home. Some persons described Swamiji’s poster as ‘life-sized’ but it measured only 22 x 30 inches. It was kiosk size, not billboard size.

In style, the lithograph of Swamiji was comparatively discreet and executed in good taste. Goes Litho Company printed many posters for the World’s Columbian Exposition, and reproductions of its Chicago Day poster are still available.34 They also printed posters for Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. The paper was relatively flimsy, 50 lb., so it could be easily pasted. Agents for these posters knew where to place them to attract attention.

All strength and success be yours

is the constant prayer of your

friend, Vivekananda.

When did Swamiji first see the poster of himself? He must have had a shock when he returned from the empty, snow-swept plains of Kansas on 2 December to see his portrait plastered along Chicago streets in places where theatrical attractions were usually advertised.35 Assuming that Slayton himself had rented the 2000-seat auditorium of the Central Music Hall for Swamiji’s talk, it appears that he was taking no chances on ticket sales.

On 6 July 1894 the Indian Mirror reported on a meeting that took place at the Minerva Theatre in Calcutta on 14 May and in this account it clarified Dharmapala’s earlier alleged remarks about Swamiji’s poster stating sensibly: ‘The picture of Swami Vivekananda was placarded all over the city of Chicago, with the advertisement announcing that he was to deliver lectures at such and such place on such and such a subject.’36 This explanation suggests to me that a strip of paper with the venue details was pasted over the poster, and this smaller type was what pedestrians paused to read. Dharmapala’s remarks, as they were reported by the Mirror, appeared to suggest that posters of Swamiji coincided with the Parliament of Religions, but Dharmapala was under no obligation to present Swamiji’s achievements in chronological order

The artist who executed the crayon drawing for the poster is unknown, but may also have had studio space in the Central Music Hall. Swamiji is basically well drawn, but his facial expression is rather stiff. The artist failed to capture the air of confidence expressed in his photograph . Considering the exuberant freedom exhibited by posters of the era, this work is comparatively restrained. It must have been mechanically enlarged. In Photoshop it fits the Harrison waist-length arms-crossed portrait exactly. Its caption displays the wonderfully organic, inventive typography of the 1890s. In practice, poster creation was collaborative: the artist would colorfill an outline offsite on rice paper, and the Goes employee would retouch the plate, either zinc or limestone, with Korn’s litho crayons finishing all colors and edges. It was printed on a flat bed, steam-driven press. A separate plate was created for each color, and each sheet was hand registered and dried between colors.37 Swamiji autographed the copy that is held by the Vedanta Society of Berkeley. It is inscribed to Hollister Sturges, ‘All strength and success be yours is the constant prayer of your friend, Vivekananda.’ Even though it is now faded, this ephemeral paper portrait from the 1890s, the great heyday of the art lithograph poster, is a national treasure. As a work of art, the Goes poster might be regarded as Orientalist, but considering how Swamiji actually dressed and comported himself in the West, it is a faithful presentation of his larger than life personality.

Study of the dissemination and repetition of Swamiji’s ‘Chicago pose’ over the years in India constitutes a separate chapter in the life of this icon.

(Concluded.)

References

23) East Meets West. Chetanananda, 2nd Ed. p. 66.

24) Eoline, “A publishing rivalry in Chicago,” Vivekananda Abroad A Postcard Pilgrimage, posted 3 January 2017. https://vivekanandaabroad.blogspot. com/2017/01/chicago-il-december-1893.html

25) Snow was skilled at manipulating negatives in the darkroom. Evidently she painted out the background of the second exposure of the group of Indian delegates to create two individual photographs of Vivekananda and Dharmapala. Snow’s signed portrait of Vivekananda also had its background painted out. Snow’s skill at altering photos was described in “Copyright Matters,” The Publishers Weekly: Volume 54 January 1, 1898 pp. 1076, 1077.

26) Snow filed a lawsuit on 20 January 1894 against persons who were copying her work. United States Circuit Court of Appeals Reports V39 (Rochester, NY: Lawyers Cooperative Publishing Co. 1900) p. 311.

27) Snow added a chain with a Greek cross to the photo of Dharmapala printed in the Portfolio of Photographs of the World’s Fair No. 10, (Chicago, The Werner Company & Maine Central Railroad: 1894). The same chain and cross was double-exposed on the photo of a tea merchant paired with Virchand Ghandi.

28) “Setting the type for a single page costs but a few dollars, but it may contain a fine wood engraving which alone costs a couple of hundred dollars.” Los Angeles Herald, 6 August 1893, p. 9.

29) Vivekananda in Indian Newspapers (1893-1902). Sankari Prasad Basu, Ed. (Calcutta: Dineshchandra Basu, Basu Bhattacharya & Co. Ltd. 1969) p. 17. Digital Library of India Item 2015.125298

30) Ray Ellis, “Swami Vivekananda in Chicago” Vedanta Kesari, August 1995, p. 310.

31) Members of the public certainly attended the talks at the Parliament of Religions, but that free event was not at all like a lecture that the public had to buy tickets for. Swamiji’s lectures at the Masonic Temple and other places in Chicago prior to 4 December were sponsored by various clubs, churches and charitable organizations.

32) Reminiscence of Josephine MacLeod, p. 247. Pravrajika Anandaprana, “Swamiji in Southern California,” Vedanta and the West, (NovemberDecember 1962) 39-40.

33) A letter from Mrs. S. K. Blodgett to Josephine MacLeod dated September 2, 1902. Prabuddha Bharata, July 1963.

34) “Goes Lithographing Company–printers of the trade since 1879”: http://news.goeslitho.com/the-historyof-goes/. Accessed 5 October 2018.

35) Swamiji gave a talk on “The Manners and Customs of India” in Hiawatha, KS on 1 December 1893. Kansas Democrat (Hiawatha, KS: 14 December 1893) p. 6.

36) Vivekananda in Indian Newspapers (1969). Basu, Ed. p. 28.

37) Charles B. Goes IV believes that in 1893 his greatgrandfather used both limestones for smaller images and zinc plates for large images. Email to author, 8 October 2018.

Source : Vedanta Kesari, October, 2019

Leave A Comment