Students of the present day have an infinite amount of information, if not wisdom, available to them at the click of a mouse. But the credibility of the information they get is questionable, as is their ability to analyze and utilize the information for their particular purpose and level of understanding. As such, the role of the teacher, as a source of wisdom and as a mentor to channel, filter, and adapt the information to each student’s level of understanding, is indispensable. Needless to say, since education in recent times has become a mere commodity, the resulting change in perspective has led to a loss of the respect that teachers ought to receive from their students. What really needs to be done is to re-infuse the system with ancient values which are sometimes regarded as old-fashioned. The need of the hour is an educational system that can revive the guru-shishya parampara in the true spirit of the term, though with a modern touch, where the teacher epitomizes knowledge, morals, values, ethics, love, and concern, and the student is a keen and respectful learner who trusts the teacher to lead him on the right path.

The Ideal Teacher-Student Relationship – The Key to Education

Swami Vivekananda said, ‘My idea of education is personal contact with the teacher—Gurugriha-vasa. Without the personal life of a teacher there would be no education.’1 The guru, the venerated teacher, is often adored in our tradition because he imparts meaning and value to existence. The shishya, the humble student, is expected to be an avid learner who can assimilate the teacher’s thoughts, ideas and insights. It is the teacherstudent relationship that primarily governs education, whether in a secular, moral, or spiritual context. The ideal teacher-student blend is a prerequisite for any educational system to achieve its objectives.

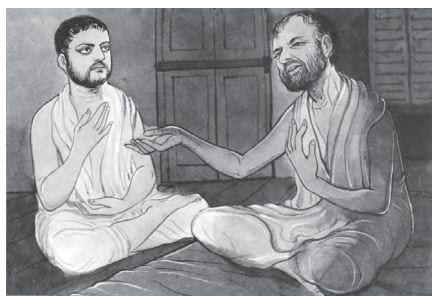

The guru-shishya relationship, a divine link that holds together the past and the future, has been the foundation of our educational system since ancient times. Many instances of great men emerging from such noble teacherstudent relationships have been extolled in our scriptures and exemplified by Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Swami Vivekananda in recent times. Sri Ramakrishna was a teacher par excellence because he practiced what he preached, and he preached only after rigorous experimentation, intense practice, and self-realisation. Swami Vivekananda, the Messiah born to teach the world as his Master had ordained him, was an ideal student who sat patiently at the feet of his Master for five years to transform himself from Narendra, the aspirant, into Swami Vivekananda, the spiritual luminary, a patriotprophet and the harbinger of a unique educational philosophy that has man-making as its objective.

Swami Vivekananda said, ‘That new life-force which he [Sri Ramakrishna] brought with him has to be instilled into learning and education, and then the real work will be done.’2 The circumstances that led Swami Vivekananda to make this statement will be understood through a brief analysis of how Sri Ramakrishna the teacher and his student Swami Vivekananda regarded each other, and how Swami Vivekananda evolved. This will also help teachers, students, and educationists to gain inspiration and encouragement in their respective roles.

Swami Vivekananda had all the hallmarks of an ideal student—self-sustaining perseverance, enthusiasm, humility, and the scientific temper to test every belief and claim that he encountered in the course of his quest for knowledge. When he met Sri Ramakrishna for the first time, hoping to get some private instruction, he was surprised to find Sri Ramakrishna shedding profuse tears of joy upon seeing him and addressing him as though he was quite familiar. All-knowing teacher that he was, Sri Ramakrishna instantly identified the student as that ancient sage Nara, the incarnation of Narayana, born on earth to remove the miseries of mankind. But the student had to pass through some preliminary stages before he could realise the power, influence, and potential of the teacher and comprehend his invaluable teaching. At first, Narendra considered Sri Ramakrishna stark mad for addressing him thus. During their next meeting, noting the Master’s behaviour and his simple language, he wondered, ‘Can this man be a great teacher?’3 When he heard Sri Ramakrishna assert that he had seen God and that religion was a reality to be perceived in an infinitely more intense way than one can sense the world, Narendra was impressed. He believed that the Master was speaking ‘not like an ordinary preacher, but from the depths of his own realizations.’4 Yet he could not reconcile the Master’s words with his strange conduct; he concluded that Sri Ramakrishna must be a monomaniac. Nevertheless, he acknowledged the magnitude of the Master’s renunciation and thought that, even if insane, this man was the holiest of the holy. On their third meeting, when Sri Ramakrishna by a mere touch shattered Narendra’s strong mind and gave him a novel experience in which the whole universe seemed to merge in an all-encompassing mysterious void, Narendra began to wonder if Sri Ramakrishna could be so easily dismissed as a lunatic. He was unable to ascertain the Master’s true nature.

The next five years saw Narendra testing his Master every inch of the way, putting his every word and every action to the test. Sri Ramakrishna heartily approved. He was always pleased whenever his disciples tested his statements or behaviour before accepting his teachings. In fact, he forbade his students to accept anything without repeated verification. He used to say: ‘Test me as the moneychangers test their coins. You must not accept me until you have tested me thoroughly.’5 Sri Ramakrishna was always patient, forgiving, humorous, and full of love. He never asked Narendra to abandon reason, and faced his arguments with patience.

Narendra’s final test was at the Cossipore garden house, when the Master was in imminent danger of passing away. He thought, ‘If he now says in the midst of the throes of death, in this terrible moment of human anguish and physical pain, “I am God Incarnate”, then I will believe.’ No sooner had Naren thought this than the Master turned towards him and, summoning all his energy, said, ‘O my Naren, are you not yet convinced? He who was Rama, He who was Krishna, He himself is now Ramakrishna in this body.’6 At this Narendra was struck dumb. Years later, at the house of Navagopal Ghosh, a householder devotee, Swami Vivekananda composed the salutation verse on Sri Ramakrishna, wherein he declared the Master to be avatara varishtha, the greatest among all incarnations.

Thus we see Narendra, the student, passing through several phases of evaluating the teacher and his teachings before deciding on the real nature of his Master—first considering him to be stark mad, then a monomaniac, then a very holy person, and then years later finally declaring him to be supreme among avataras. But the Great Master was able to identify the character, traits, and personality of his student at their very first meeting, and consistently maintained that outlook.

There are many lessons we can draw from this exceptional teacher-student relationship. We find that Sri Ramakrishna encouraged Naren to be independent in his thinking. The student was led from doubt to certainty, from darkness to light, from anguish of mind to peace of vision and bliss of Spirit, and from the pale of a little learning to omniscience. All this was in gradual yet steadily advancing steps. The teacher’s love and faith in the student worked as a restraint upon the latter and became a strong shield against the temptations of the world. Occasionally, Sri Ramakrishna would also not hesitate to reprimand Naren, though it was only to facilitate the student’s progress in the right direction. On the training that he received, Swami Vivekananda once remarked, ‘As the master wrestler proceeds with great caution and restraint with the beginner, now overpowering him in the struggle with great difficulty as it were, again allowing himself to be defeated to strengthen the pupil’s selfconfidence – in exactly the same manner did Sri Ramakrishna handle us . . . He would keep us under control by carefully observing even the minute details of our life. All this was done silently and unobtrusively. That was the secret of his training of the disciples and of his moulding of their lives.’7

Perfect teacher that he was, Sri Ramakrishna never laid down identical disciplines for his students, whom he very well knew to have diverse temperaments and backgrounds. But he kept a strict eye on their practice of discrimination, detachment, self-control, and meditation. Sri Ramakrishna often used to get involved in absorbing group discussions with his students, exchanging ideas and views with them without any inhibition and letting them share their distinctive views quite openly. If differences of opinion arose among them, invariably Sri Ramakrishna would reconcile their differences in a very convincing manner. Thus we see that the teacher identified the aptitude and level of each of his disciples individually, and raised them from their own standpoints. Swami Vivekananda said, ‘His very method of teaching was a unique phenomenon…. He never destroyed a single man’s special inclinations. He gave words of hope and encouragement even to the most degraded of persons and lifted them up.’8 The result was that all his students became holistic personalities, each in his own unique way, and contributed immensely to the welfare of society. A wonderful teacher in every sense of the word, the Master’s thoughts, words and deeds were all in harmony. Although the relationship between Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda flourished in a spiritual context, it should be noted that the approach is equally applicable, if not more so, in a secular context.

As we explore this divine relationship further, we discover some distinctive characteristics that are fundamental for our approach to education, but are completely ignored in the present-day materialistic approach.

Education – A Life-long Process of Learning

Swami Vivekananda, quoting a profoundly insightful statement of Sri Ramakrishna, once said, ‘There are many things to learn, we must struggle for new and higher things till we die—struggle is the end of human life. Sri Ramakrishna used to say, “As long as I live, so long do I learn.”’9 To the common man the process of learning is completed with graduation from college; but for the true aspirant to wisdom who possesses a broader perception of knowledge, learning is a lifelong process. In reality, real education commences only after one gets a degree! Life is a continuous progression of learning through experiences, both good and bad. Great teachers like Sri Ramakrishna could make bold declarations from their experiences of a lifetime, which have today enriched the lives of millions across the world and will continue to do so in centuries to come. A glance through The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna or The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda will amply confirm this truth. The texts are replete with anecdotes, parables, stories, conversations, etc., which are based on mundane experiences.

Many of us may have undergone such experiences. They may seem like mere incidents to us, whereas for seers like Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, they were pointers to subtle truths. To observe ordinary events, to draw profound conclusions from them, and to pursue them in life is the hallmark of the truly learned. Interestingly, we need to distinguish being ‘literate’ from being ‘educated’. A ‘literate’ person knows how to read and write, may perhaps acquire a degree, and then use that knowledge to earn a livelihood. He can do nothing more. An ‘educated’ person, on the other hand, has acquired insight, wisdom, the power of discrimination, and the ability to lead a blissful life, despite the inevitable trials and tribulations he will encounter. Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda lived as exemplars to show us that education is such a life-long process of learning—and, more significantly, a life-enriching process.

Education – A Means of Self-Discovery

Conversations with Sri Ramakrishna often evoked the spirit of inquiry in Swami Vivekananda. Sri Ramakrishna’s influence on him was subtle and steady; he often let his disciple discover the truth for himself. This process of self-discovery enabled Swami Vivekananda to declare with conviction in later years that knowledge is inherent in every human being and requires self-effort for its manifestation. He declared, ‘What a man “learns” is really what he “discovers”, by taking the cover off his own soul, which is a mine of infinite knowledge.’10 This suggests that the task of the teacher is only to help the child to manifest his knowledge by removing the obstacles in his path. Swami Vivekananda further said: ‘Within man is all knowledge— even in a boy it is so—and it requires only an awakening, and that much is the work of a teacher.’11

To drive his point home, he refers to the growth of a plant. One cannot do anything more to a plant than provide it with water, air, and manure. It grows and absorbs all that it needs by its own nature. Even so is the case with a child. We find that the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda exemplar of imparting education is a reflection of the selflearning process expounded in our scriptures by the method of shravana, manana and nididhyasana. These correspond to listening to the teaching; reflection upon the teaching; and a deep and repeated deliberation, through a rational and cognitive process, on what has been taught. As he understood human limitations very well, Sri Ramakrishna never imposed his views directly on others. He wisely adapted his teaching to the mindset of his students, who included both scholars and illiterates. He taught even the most abstract and complex ideas in the simplest of terms, interspersing them with healthy doses of humour, and aroused his students’ capacity to think for themselves.

Religion – The Innermost Core of Education

The next significant aspect of the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda perspective on education is the perception that religion is the innermost core of education. Swami Vivekananda said, ‘Education, intelligence, and thought are all spiritual, all find expression in religion.’12 Certainly no particular religion was meant, for Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda personified the harmony of religions. ‘Religion as the innermost core of education’ therefore signifies that learning should enable students to identify the divinity inherent within themselves. Education should provide the essential training that enables them to lead lives that manifest their higher nature. All impulses, thoughts, and actions which lead towards this goal of manifesting their higher nature are naturally ennobling and harmonizing; they are considered ethical and moral in the truest sense. Swami Vivekananda reminds us time and again that religion does not consist of dogmas or creeds or any set of rituals. It is in this context that his idea of religion as the basis of education should be understood.

We note that, in Swami Vivekananda’s interpretation, religion and education share an identity of purpose. The reason why religion forms the very foundation of education becomes clear in his own words: ‘In building up character, in making for everything that is good and great, in bringing peace to others and peace to one’s own self, religion is the highest motive power and, therefore, ought to be studied from that standpoint.’13 Swami Vivekananda believed that if education with its religious core can invigorate man’s faith in his divine nature and energize the infinite potentialities of the human soul, it is sure to help man become strong, tolerant, and sympathetic. It would also help man to extend his love and good will beyond communal, national, and racial barriers. The educational process should therefore strive for a synthesis of spirituality and science; as Dr. Albert Einstein averred, ‘Science without religion is blind, and religion without science is lame.’

Human Excellence – The Target of Education

The spirit of true education is found in the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda perspective which maintains that human excellence is the objective of education. It thereby signifies a simultaneous and harmonious development of body, mind, and soul. It affirms that education becomes complete when knowledge rises to the level of wisdom. The art of educating a person lies in the method of investigating the powers of the inner man, and in the knowledge of his inherent potentialities. These are capacities which are also responsible for the objective investigations of scientists. Modern methods of education can never be satisfactory so long as the development of inner culture and the central facts governing life are ignored. Education should develop moral strength and inner toughness through a well-regulated and disciplined life. In the present-day scenario, when all indicators of social and economic development are showing an upward trend, we should be cautious that these material achievements have not been gained at the cost of our inner growth, culture, values, traditions, and human relationships. Physical health, mental purity, intellectual acuteness, moral power, and a spiritual outlook on life should go together if perfection is to be achieved. Education should enable students to be adherents of satya and dharma, observers of continence and followers of a righteous mode of living.

As Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru fittingly pointed out, ‘Men like Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, men like Swami Vivekananda….are…great constructive geniuses of the world not only in regard to the particular teachings that they taught, but (in) their approach to the world; and their conscious and unconscious influence on it is of the most vital importance to us.’14 Let all stakeholders in education respond dynamically to the call of educational renaissance so perfectly exemplified in the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda model.

References

- The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Mayavati Memorial Edition, January 1989, 5.224. (Hereafter, CW)

- Ibid, p. 370

- The Life of Swami Vivekananda, by His Eastern and Western Disciples, 6th edition, 1.77

- Ibid, 1.77

- Ibid, 1.97-98

- Ibid, 1.183

- Ibid, 1.131-32

- CW, 7.171

- Ibid, 4.477

- Ibid, 1.28

- Ibid, 5.366

- Ibid, 5.519

- Ibid, 2.67

- Great Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, p.121

Source : Vedanta Kesari, December, 2016

Leave A Comment