ON 8 NOVEMBER 2010 United States President Barack Obama addressed the Indian Parliament:

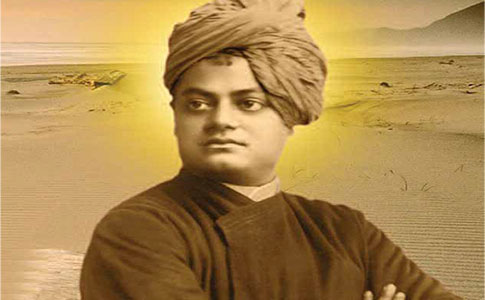

Instead of succumbing to division, you have shown that the strength of India—the very idea of India—is its embrace of all colors, all castes, all creeds. [Applause.] It’s the diversity represented in this chamber today. It’s the richness of faiths celebrated by a visitor to my hometown of Chicago more than a century ago—the renowned Swami Vivekananda. He said that, ‘holiness, purity and charity are not the exclusive possessions of any church in the world, and that every system has produced men and women of the most exalted character.’1

Swami Vivekananda’s words are as soul-stirring today as they were in 1893, a significant testament to his impact on America.

‘I Form no Sect’

Over a hundred years ago Americans were taken by surprise when this foreigner aroused and inspired them with the message of their innate divinity, the goal of God-realization, the unity of existence, and the harmony of religions. At the end of the swami’s message a stampede of women climbed across the parliament benches just to get closer to the man of God who had uttered it. Such was Vivekananda’s impact that in 1976 the Smithsonian Institution recognized the swami as one of twenty-nine eminent foreign visitors, who at the 1893 Parliament of Religions ‘charmed audiences with his magical oratory, and left an indelible mark on America’s spiritual development.’2

What are some of the signs of that mark? First of all, Vedanta is in America to stay. ‘As an Oriental religious group preaching an alien message in an oft en hostile environment,’ historian Carl Jackson explained, ‘this has been a considerable achievement.’3

Most new religious movements collapse within a single generation. [However, the Vedanta Movement] has established firm foundations and is today in more flourishing condition than it has ever been. It has won increasing public acceptance, integrated a far-reaching movement and found necessary channels to the outside public (ibid.).

How did a non-indigenous religious tradition become a visible and successfully integrated presence in a predominantly Judeo-Christian country? In a 1 October 2011 New York Times article ‘How Yoga Won the West’, Anne Bardach explained how Vivekananda’s magnetic personality and spellbinding message of the divinity of the soul captivated Americans as he lectured the length and breadth of the Yankee land. And along with that, Vivekananda’s ‘prescription for life was simple, and perfectly American: “work and worship”. ’4

However, Americans’ attraction to this modern-day rishi lays not only in Vivekananda’s powerful delivery, nor even in his message of God-realization and the practical methods to attain it. During the swami’s ‘Address at the Final Session’ of the Parliament, Americans heard for the first time the peace-giving truth of religious harmony—a message that would sweep across their land well into the twenty-fi rst century: ‘Do I wish that the Christian would become a Hindu? God forbid. Do I wish that the Hindu or Buddhist would become Christian? God forbid. … But each must assimilate the spirit of the others and yet preserve his individuality and grow according to his own law of growth.’5

For Americans this was an altogether nonproselytizing and, therefore, non-threatening invitation to open their hearts and minds to an ancient non-sectarian tradition and drink in its unadulterated waters of spirituality. In so doing, they had nothing to lose, yet everything to gain. Is it any wonder that Vivekananda is recognized for his ‘significant contribution to the understanding of Vedanta in the Western world?’6

Because Vivekananda founded his American roots as ‘Vedanta’—rather than the more culturally-loaded term ‘Hindu’—Societies, Westerners were able to resist their knee-jerk reaction to reject what was too foreign-sounding and therefore alien. ‘I form no sect, nor organization,’ Vivekananda promised.⁷ Instead, his Western mission was clear from the start: ‘I propound a philosophy which can serve as a basis to every possible religious system in the world’,8 which in America at that time spoke to Christians and Jews.

Furthermore, by publishing his four yogas, Vivekananda answered America’s need to explore the essence of Vedanta in a language they could understand. And thus, as the swami prophesied, his written works would ‘make out of dry philosophy and intricate mythology and queer startling psycholog y, a religion which shall be easy, simple, popular, and at the same time meet the requirements of the highest minds’ (5.104). In fact, after Vivekananda’s Harvard lecture in 1896, William James and his colleagues invited the turbaned monk to chair Harvard’s new department, an invitation that was promptly followed by Columbia University’s own offer. But due to his vows of renunciation, Vivekananda declined them both.

The fact that Swami Vivekananda neither proselytized, converted, nor charged for spirituality was refreshing to Americans, sixty percent of whom would later leave organized religion during America’s ‘Great Church Exodus’ of the 1960s, due to their disenchantment with the Judeo-Christian church authority, dogma, and its business of religion. Since the 1960s American scholars and clerg y alike regard Vedanta as the offi cial voice of Hinduism,9 largely due to Vivekananda’s impact at the 1893 Parliament and the standard he set for his emissaries and mission in America.

Yet we might as well ask, how can Vedanta present itself to the West as both Hindu and non-sectarian? Th e Vedanta movement introduced to the West a revitalized Hinduism, bereft of priestcraft , kitchen-religion orthodoxies, or any other superstitious dogmas, but solidly rooted in India’s Sanatana Dharma, which from ancient times has shown that it transcends racial, national, and sectarian boundaries. In this special sense Vedanta is both the youngest religion and the oldest religion of the world. It can and does, therefore, represent both non-sectarianism and Hinduism, features that have given it a broader appeal and special status (85–7,144).

‘You Are not Your Mind’

Other factors of the Vedanta movement’s success in America were its substantial literary movement and the publicity Vivekananda and the early pioneer swamis received from prominent Americans. In a 29 March 2012 article in the Wall Street Journal by A L Bardach, the bold headlines read: ‘What Did J D Salinger, Leo Tolstoy, Nikola Tesla and Sarah Bernhardt Have in Common?’ And the subtitle reads: ‘The surprising—and continuing—influence of Swami Vivekananda, the Pied Piper of the Global Yoga Movement.’ The article—illustrated with the photo of Vivekananda seated in meditation along with close-ups of his famous followers—primarily focused on J D Salinger’s fascination for Vedanta: ‘After an initial dalliance in the late 1940s with Zen—a spiritual path without a God—Salinger discovered Vedanta, which he found infinitely more consoling. “Unlike Zen,” Salinger’s biographer, Kenneth Slawenski, points out, “Vedanta offered a path to a personal relationship with God. … [and] a promise that he could obtain a cure for his depression. … and find God, and through God, peace.”’10

Bardach then fleshed out her article by adding how Vivekananda’s influence blossomed well into the mid-twentieth century, ‘infusing the work of Mahatma Gandhi, Carl Jung, George Santayana, Jane Addams, Joseph Campbell and Henry Miller, among assorted luminaries’ (ibid.).

In the 1980s Vivekananda seemed to be eclipsed by what Bardach called ‘American baby boomers—more disposed to “doing” than “being”,’ and who ‘opted for “hot yoga” classes over meditation,’ thus morphing his spiritual teaching ‘into a fitness cult with expensive accessories.’ However, undaunted by this passing phase, Bardach highlighted instead Vivekananda’s inherently long-lasting appeal. ‘If there were a single takeaway line that boils down his teachings to one spiritual bullet point,’ Bardach asserted, ‘it would be “You are not your body”.’ This might be bad news for the yoga-mat crowd. The good news for beleaguered souls like Salinger was Vivekananda’s corollary: ‘You are not your mind.’ What then was and is the key to Vivekananda’s success in the West? Bardach posited: ‘Vivekananda’s genius was to simplify Vedantic thought to a few accessible teachings that Westerners found irresistible’ (ibid.).

God was not the capricious tyrant in the heavens avowed by Bible-thumpers, but rather a power that resided in the human heart. ‘Each soul is potentially divine,’ Vivekananda promised. ‘The goal is to manifest that divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal.’ And to close the deal for the fence-sitters, he punched up Vedanta’s embrace of other faiths and their prophets. Christ and Buddha were incarnations of the divine, he said, no less than Krishna and his own teacher, Ramakrishna (ibid.).

Carl Jackson also noted that the success of the Vedanta movement in America has depended heavily on its attempt to adapt to Western conditions such as its Protestant-style Sunday morning sermons and weekly classes.11 This standard was set by Vivekananda himself, who adopted the Western-style lecture format throughout America and eventually started weekly classes for more dedicated seekers in New York.

Jackson noted that from the 1930s to the 1950s the typical Vedanta members were middle class and upper-middle class families—mostly adults with a disproportionate number of females in a ratio of two to one (97–8). The average spiritual seeker was from a Protestant background and some were connected with Theosophy, New Thought, Spiritualism, or Christian Science (98). Of the 1950s testimonials contained in What Vedanta Means to Me, Vedanta’s greatest appeal was its universality versus Western Christianity’s dogmatism, an appeal that remains popular today (100). Danielle Gaither, a college student at the University of North Texas in Denton, recently shared her attraction:

One thing I really like about Vedanta is that there isn’t One True Way to practice it. People are encouraged to find what combination of the different Yogas works for them. Also, the Vedanta Society is the only spiritual community where I’ve felt that my entire self is welcome. In every other path I’ve tried, I’ve felt that I had to leave some parts of myself at the door, like my political beliefs or my critical thinking skills.12

‘I Believe that too’

Another key to the Vedanta movement’s success is its practical, experiential methodology and direct mystical approach. Christopher Isherwood vouched: ‘Vedanta made me understand for the first time that a practical, working religion is experimental and empirical. You are always on your own, finding things out for yourself in your individual way.’13 For others, it is Vedanta’s psychological insight and positive understanding of human nature that provides a therapeutic perspective for spiritual growth. For still others, former Christians and Jews have found that through their contact with Vedanta, they then developed a renewed respect for fundamental teachings of Christianity and Judaism. Playwright John van Druten mentioned that after his introduction to Vedanta, he could ‘turn back’ to Christianity, discovering ‘much more’ than he had ‘ever suspected of existing’ (101).

Unlike many Indian immigrants in America, American-born Vedantists are more drawn to Vedanta’s interreligious and academic mission in the West. On the one hand, native-born Hindus have little interest in interreligious exchange with Christians or Muslims, who have too often historically scorned their religion and desecrated their temples. But on the other hand, Westerners embrace comparative religions and interfaith venues because this is often how they are introduced to Vedanta. Once they become committed Vedantists, Westerners feel that such academic and interfaith outreach connects their Vedanta tradition with American society in a broad and healthy way; in fact, it prevents Vedanta from becoming just another cosy, insulated Hindu cult with no recognized standing or voice in their own culture and society. Furthermore, most Westerners take pride in Vedanta’s seminal role in interreligious dialogue and sincerely seek to understand how their religion holds up against other religious traditions of the world. In the process they often find that a meaningful spiritual exchange of fundamental perspectives amongst religious traditions deepens and broadens their own Vedanta perspective. In order to explain Hinduism to other curious Americans, they, in turn, are forced to deepen their own understanding of Vedanta.14

Because of the American Vedanta Societies’ continued commitment to interreligious dialogue, Jewish and Christian spiritual leaders have also found their own rapport with Vivekananda’s life and teachings. Rabbi Henoch Dov Hoffman, psychiatrist and Hasidic Jewish representative of the renowned Snowmass Conference, who was invited to participate in a Vedanta Society retreat at Olema, in northern California, affirmed that he often quotes Vivekananda’s teachings to members of his own synagogue.15 Rabbi Rami Shapiro, renowned lecturer and author, also professes a deep connection with Vivekananda and Vedanta. ‘The realization and the expression of Brahman as Atman speak to me on so many levels,’ Shapiro explained, ‘but most of all it addresses the moral challenges of life. I come from a tradition of law and commandments, but this rests on the authority of God and revelation, neither of which speak to me. I do not believe in a god somewhere, but in the Divine Reality that is everywhere and everything.’

‘But that is not why I pursued initiation,’ the rabbi continued. ‘It is not enough that I know the principles of Vedanta. When I looked to the heroes of Vedanta—Ramakrishna, Sarada Devi, Vivekananda—I found the kinds of people I myself wish to become.’16

In June 2009 the Northaven United Methodist Church, in Dallas, Texas—in the conservative heart of America’s ‘Bible Belt’—invited Vedanta to participate in its monthly interfaith ‘Contemplative Life Series’.Bob Stewart, chairman of the series, frankly admitted: ‘Some Methodists are dissatisfied with the lack of any kind of spiritual practice in the Methodist Church.’ During these monthly gatherings of two hundred seekers—Methodist and non-Methodist, churched and unchurched—members of the audience have subsequently requested interviews at the local Vedanta centre, including Christian ministers, theologians, and missionaries, and a sixteen-year-old boy who heard about Vedanta for the first time with his mother. The boy was so moved by the message of Vivekananda that he could not sleep that night. Th e next morning he wrote: Dear Member of the Vedanta Society—

My name is Conner Gillette and I have recently attended Th e Contemplative Life presentation. After going to a Christian church my whole life, I have started to question why only Jesus is the way to heaven, when so many other faiths seem to have righteous qualities and aims toward the betterment of humanity. It didn’t seem that only one faith had it correct and the rest are going to hell, no matter how just of a faith or person they were. I need to follow the urgings [sic] of my heart, and it urges me to fi nd truth and love, in whatever form it presents itself and to live by it. Aft er hearing the talk on Vedanta, I feel that this is a form of truth that computes with my emotion, my intellect, and my heart. I would like to make an appointment to learn more of this philosophy and its practices.

Thank you from my heart, Conner Gillette.1⁷

Four months later, Conner was initiated. Not all interreligious or academic events are necessarily inspired, congenial, or even nonconfrontational encounters. However, some of the most stimulating have been the tri-annual visits to the Santa Barbara Vedanta temple of the sociolog y classes from Westmont College, one of the foremost Christian missionary colleges in America. The students are intelligent, well-versed in Christian scriptures, sometimes dogmatic and, therefore, markedly challenging. Once, when Bible’s teaching ‘Ye are gods; and all of ye are children of the most High’ 18 was used to clarify Vedanta’s belief in the divinity of the soul, a bitter debate ensued from the visiting students over the ‘correct’ intent of Christ’s words ‘Ye are gods’.19 Finally, one student arose and challenged his fellow students: ‘If there is no interfaith council here in this city, these comparative religions classes provide us with the same benefit.’ He then bravely stated: ‘Many of us have been trained to think that there is only one belief. But this class has shown us that there are other paths.’20 The class was silenced; all of us deeply moved by this hard-won and broadening outcome. Thereafter, each year students from Westmont College visit the Vedanta temple in

Santa Barbara to interview the nuns for their term papers on Vedanta philosophy.

As Vedantists we should never mind if our message of Vedanta arouses a strong reaction in our audience. Questions may come from people’s ignorance or prejudice, but aside from his sometimes cutting rebukes, Vivekananda could also react with sympathy or humour. At Thousand Island Park Miss Dutcher, a staunch Methodist and the hostess at the cottage where Vivekananda delivered his Inspired Talks, would often become so distressed at the swami’s revolutionary ideals that she would disappear for two or three days at a time. But Vivekananda would explain to others in his class: ‘Don’t you see? … This is no ordinary illness. It is the reaction of the body against the chaos that is going on in her mind. She cannot bear it.’21

Often, when Vedanta representatives speak before high school or university classes—whether they are psycholog y, sociology, anthropolog y, ecolog y, Asian studies, spirituality, or comparative religions classes—instructors sometimes share their students’ candid reactions. Recently, aft er an introductory Vedanta presentation at a World Religions class of divinity school graduates at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, the professor shared his students’ responses, the following three of which were representative of the class’s reactions:

Ryan: ‘I like Hinduism’s inclusivity. I like the idea that God is in everyone. And the next time I feel frustrated with someone, I’m going to try to remember this.’Christina: ‘The concept of having many gods who are manifestations of the supreme God, Brahman, is compelling. Hinduism understands inclusive spirituality with both feminine and masculine embodiments of God.’Scott: ‘For me personally I felt the explanation of Vivekananda’s four yogas was truly insightful and are methods we should apply to the Christian religion.’22

Today, no matter where in America, when strangers ask ‘What are your beliefs?’ and I reply ‘All religions lead to the same Truth,’ invariably their heads nod in assent, ‘Yes, I believe that too!’ Somehow this never ceases to amaze me. What was once considered unthinkable before Vivekananda’s advent is now accepted as American mainstream thought. Indeed, Vivekananda has left , and continues to leave, an indelible mark on America’s spiritual development.

(Source: Prabuddha Bharatha January 2013)

Notes and References

1. <http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-of-fice/2010/11/08/remarks-president-joint-session-indian-parliament-new-delhi-india> accessed 31 August 2012.

2. ‘Abroad in America’, National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, 1976.

3. Carl T Jackson, The Swami in America: A History of the Ramakrishna Movement in the United States (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1969), 617–18.

4. The New York Times, 2 October 2011; available at <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/02/opin-ion/sunday/how-yoga-won-the-west.html> ac-cessed 31 August 2012.

5. The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, 9 vols (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1–8, 1989; 9, 1997), 1.24.

6. Father Th omas Keating’s endorsement in Vedanta: Voice of Freedom, ed. and comp. Swami Chetanananda (New York: Philosophical Li-brary, 1986).

7. Marie Louise Burke, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discoveries, 6 vols (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1985), 3.326.

8. Complete Works, 5 . 1 8 7.

9. Carl T Jackson, Vedanta for the West: The Rama-krishna Movement in the United States (Bloom-ington: Indiana University, 1995), 144.

10. The Wall Street Journal, 29 March 2012; avail-able at <http://online.wsj.com/article/SB100 01424052702303404704577305581227233656.html> accessed 31 August 2012.

11. See Vedanta for the West: The Ramakrishna Movement in the United States, 138.

12. Testimonial submitted for publication in 2010.

13. Vedanta for the West: Th e Ramakrishna Move-ment in the United States, 100.

14. Research gathered from conversations and interviews.

15. Conversation at Snowmass Conference’s Men-toring Retreat, Colorado, June 2010.

16. Testimonial submitted for publication in 2010.

17. Email correspondence, 6 June 2009.

18. Psalms 82:6.

19. John 10:34.

20. Private Journal, 1980s.

21. Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov-eries, 3.121.

22. Dr Ruben Habito’s class on ‘Spirituality and Re-ligion’ at Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, 2010.

Leave A Comment