NEW YORK,

1895.

The work here is going on splendidly. I have been working incessantly at two classes a day since my arrival. Tomorrow I go out of town with Mr. Leggett for a week’s holiday. Did you know Madame Antoinette Sterling, one of your greatest singers? She is very much interested in the work.

I have made over all the secular part of the work to a committee and am free from all that botheration. I have no aptitude for organising. It nearly breaks me to pieces.

. . . What about the Nârada-Sutra? There will be a good sale of the book here, I am sure. I have now taken up the Yoga-Sutras and take them up one by one and go through all the commentators along with them. These talks are all taken down, and when completed will form the fullest annotated translation of Patanjali in English. Of course it will be rather a big work.

At Trübner’s I think there is an edition of Kurma Purâna. The commentator, Vijnâna Bhikshu, is continually quoting from that book. I have never seen the book myself. Will you kindly find time to go and see if in it there are some chapters on Yoga? If so, will you kindly send me a copy? Also of the Hatha-Yoga-Pradipikâ, Shiva-Samhitâ, and any other book on Yoga? The originals of course. I shall send you the money for them as soon as they arrive. Also a copy of Sânkhya-Kârikâ of Ishwara Krishna by John Davies. Just now your letter reached along with Indian letters. The one man who is ready is ill. The others say that they cannot come over on the spur of the moment. So far it seems unlucky. I am sorry they could not come. What can be done? Things go slow in India!

Ramanuja’s theory is that the bound soul or Jiva has its perfections involved, entered, into itself. When this perfection again evolves, it becomes free. The Advaitin declares both these to take place only in show; there was neither involution nor evolution. Both processes were Maya, or apparent only.

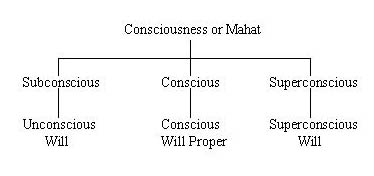

In the first place, the soul is not essentially a knowing being. Sachchidânanda is only an approximate definition, and Neti Neti is the essential definition. Schopenhauer caught this idea of willing from the Buddhists. We have it also in Vâsanâ or Trishnâ, Pali tanhâ. We also admit that it is the cause of all manifestation which are, in their turn, its effects. But, being a cause, it must be a combination of the Absolute and Maya. Even knowledge, being a compound, cannot be the Absolute itself, but it is the nearest approach to it, and higher than Vasana, conscious or unconscious. The Absolute first becomes the mixture of knowledge, then, in the second degree, that of will. If it be said that plants have no consciousness, that they are at best only unconscious wills, the answer is that even the unconscious plant-will is a manifestation of the consciousness, not of the plant, but of the cosmos, the Mahat of the Sankhya Philosophy. The Buddhist analysis of everything into will is imperfect, firstly, because will is itself a compound, and secondly, because consciousness or knowledge which is a compound of the first degree, precedes it. Knowledge is action. First action, then reaction. When the mind perceives, then, as the reaction, it wills. The will is in the mind. So it is absurd to say that will is the last analysis. Deussen is playing into the hands of the Darwinists.

But evolution must be brought in accordance with the more exact science of Physics, which can demonstrate that every evolution must be preceded by an involution. This being so, the evolution of the Vasana or will must be preceded by the involution of the Mahat or cosmic consciousness.

There is no willing without knowing. How can we desire unless we know the object of desire?

The apparent difficulty vanishes as soon as you divide knowledge also into subconscious and conscious. And why not? If will can be so treated, why not its father?

VIVEKANANDA

Leave A Comment